Finding Friends in the Icelandic Language

These are the words you like to hang out with...everyday ones

I like to think that I would have been a famous brain surgeon if I hadn’t fallen in love with my own language (okay, solipsistic, I know already) back in my 20s.

(If you already know this story, skip it.) It happened when I was working in Italy for two years in the early 1980s. I remember the moment lightning struck—at a whiteboard, between explaining would and will and all the other magical modal verbs that can change the meaning of every sentence we say (can, could, shall, should, may, might, need to, ought to). They were such common words, so integral, yet so powerful. Still waters, I thought, ran deep.

But between teaching English classes, I was also walking around Florence, listening to people behind their backs, and trying to figure out how to say things that were on my mind, but in Italian. This presented unexpected difficulties. There were plenty of familiar-sounding words in the air—famiglia, importante, abilità, ristorante, atmosfera, differente, persona, sentimenti—but where were the words I wanted for everyday life? I couldn’t find close cognate forms for the powerful, emotionally freighted words we use in English for common experiences and feelings. Language seemed to function at a more formal level in Italian than it did in English. I got used to it, eventually, but I missed what we think of as English’s simple words, what I have come to call home words. (Eventually I would write about the common verbs of this type, phrasal verbs, in my book How We Really Talk: Using Phrasal Verbs in English.)

Up to now, I might have been considered fairly multilingual for an American (we’re notoriously bad with languages). I studied Latin in high school, French in college, and learned Italian in Italy. I have a good grounding in the Romance languages, but nothing in the Germanic ones. That’s changing.

I spent three weeks last month trying to learn some German in Cologne, Germany, and I’m now enrolled in a summer Icelandic language course in Reykjavik, Iceland. Finally, I’m getting a taste of Germanic languages and, wow, I’m home.

That is to say, I am finding cognates for our everyday language and for German words all over the place.

Let me back up a little.

Iceland, or Island (pronounce the ‘s’ unvoiced, as in sell: Ees-land) was settled first by Vikings from Scandinavia probably in 874 AD. This information comes from two 12th century texts, the Islendigabók, the Book of Iceland, and the Landnámabók, or Settlement book. (These people have been serious about family history for a very long time.) This is about the same time as the Vikings were also settling on the northeastern coast and other places in the British Isles as well as North America.

The Icelandic language has a famously complex grammar, especially when compared with English. For example, our nouns in English have no gender; we don’t have masculine or feminine nouns. Icelandic has not only those but also a neutral gender, like German and Russian. In English our adjectives don’t change form at all. Tall is tall is tall, whether you’re talking about one man, two women, or three skyscrapers. But in Icelandic, an adjective might have tens of forms depending on whether it modifies a singular or plural or feminine or masculine or neuter or nominative or accusative or dative or genitive noun, or a combination of any of those (or more, what do I know?). My teacher said there are 120 possible forms for any given adjective. Not sure I believe that, but hey, it’s Iceland and the sun doesn’t set in the summer and doesn’t rise in the winter. Anything could be true.

I don’t really expect to get far with the grammar. But I can marvel at the vocabulary. Buried in Icelandic words are their English and German cousins. Many times, the words or expressions aren’t ones we would use every day, but they’re related—close kin. Even cooler, the words that we have in common go back at least 1200 years and back beyond that thousands of years to the unwritten and unattested parent language, Indo-European. Yay! I’m learning Indo-European! Sort of.

Here are some of the many cognates I’m observing; if you already know German, these will come as no surprise. But I’m easy to please.

mannkynið — mankind.

dagur — day. The /g/ is very soft, so it sounds sort of like dah-ur

í dag — today. Sounds like ee-tag, again with the very soft /g/.

goðan dag — good-day. The ð is a voiced /th/ sound, extremely uncommon; English and Icelandic have it, but most languages don’t.

á eftir — after

í morgun — this morning

í gær — yesterday (the /y/ of our “yester” and /soft g/ of “gær” are similar) — also sounds like hier in French and ieri in Italian, both meaning “yesterday.”

dottír — daughter

tala — to speak (tell)

ðu — you, or thou

skyrta — shirt

vika — week

barn — bairn, child

kona — woman, queen

bók — book

safn — museum (safe place)

barnaskóli — bairn-school (elementary school)

Unfortunately, most words are still indecipherable to me. Like Germans, Icelanders put many words together in long strings that use different word forms. My first task is simply to understand where one word ends and the next one begins. In a newspaper article today, I see the word strandveiðiútgerðar, which Google Translate helpfully tells me means “coastal fishing industry.” Okay, I can see “strand,” and vaguely remember the poetic English “strand,” or coast. I can see “út” and think it might be “out.” But the rest? Not there yet.

I understand almost no spoken Icelandic yet because, like all fluent speakers of any language, they speak too fast for a beginner like me to catch their meaning. But I’m hopeful that these three weeks, which are truly intensive, will change that.

So, four days in, I’m not where I want to be. But I’m having a hvalur of a time trying.

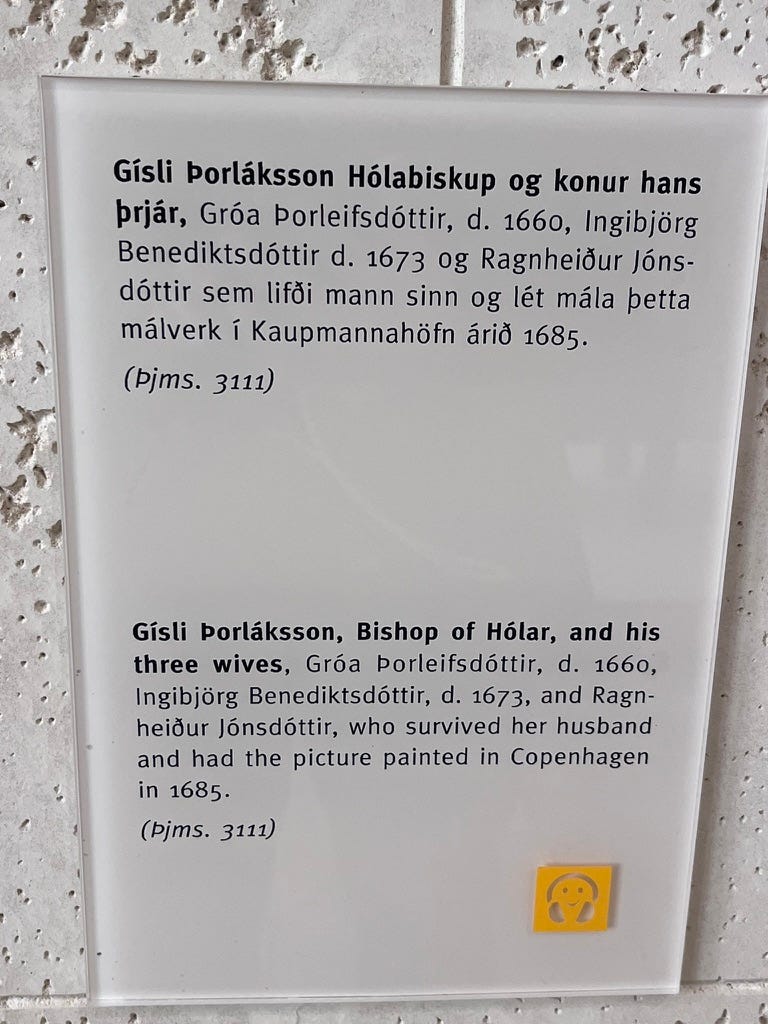

—-PS By the way, the picture at the top of this post is of a 17th-century Icelandic bishop (Lutheran, I’m guessing) and his three wives. I momentarily gasped and wondered whether the Lutherans had ever been polygamous. But no. Bishop Þorláksson did have three wives, but not all at once. Number one died, then number two died, then the bishop died, then number three (on the right) quite graciously had all four of them put into this painting.

wonderful to read about how and why you are doing this!